Jeremy Kirk, Associate Professor of Music, Southwestern College (Winfield, KS)

Introduction

It is no secret that drum circles promote a sense of community through a shared experience and foster intercultural understanding through music. Many drum circle facilitators share traditional rhythms from cultures around the globe to help achieve these benefits. This article aims to help facilitators share rhythms and culture of Hawai’i to offer their audience an additional global perspective and experience; one with an abundance of love and great respect.

Background

As a learner and practitioner of hula kahiko (pre-contact hula) and now kumu hula (teacher of hula), I have been extremely fortunate to combine my hula kahiko training with my formal western music education and experience as a teacher and professor. The cultural art forms of Hawai’i nei (beloved Hawai’i) are extremely underrepresented in western curricula and it is my passion, privilege, and kuleana (responsibility) to be able to share with my students and others across the globe.

Before we begin with teaching and incorporating traditional rhythms found in hula, we must identify our goal and kuleana. As a facilitator in this regard, our fundamental goal is to bring awareness of and respect to Hawaiian culture and help our audience understand and share the aloha spirit. We must ho’omau (perpetuate) and malama (protect) while helping others experience and share love (aloha) and mana (spiritual energy).

What is Aloha?

Many people think of Aloha as a greeting; a “hello.” While that is true, Aloha has a much deeper meaning. Aloha is love. Aloha is compassion. Mutual respect. An acknowledgement of the miracle of life. This concept is shared around the world. In Samoan culture, it is called Talofa. In Maori culture, it is Aroha. In Bantu speaking regions of Africa, it is Ubuntu.

The Hawaiian language is beautifully poetic. If we break down the word Aloha, we have “alo” and “ha.” Alo is presence, or to be in the presence of; Ha is breath, or breath of life. Aloha acknowledges that we are in the presence of the blessing of life and that we all share this breath together. In other context, Alo means “face” or “to face.” The traditional Hawaiian greeting is not to shake hands, but to face each other nose to nose and share breath through the nostrils by breathing simultaneously. Thus, Aloha.

For further context, I will share a traditional teaching of aloha that is taught to keiki (children) as they are learning their place in the world:

Aloha is being a part of all, and all being a part of me. When there is pain, it is my pain. When there is joy, it is also mine. I respect all that is as part of the creator and part of me. I will not willfully harm anyone or anything. When food is needed I will take only my need and explain why it is being taken. The earth, the sky, and the sea are mine to care for, to love, and to protect. This is Aloha.

When facilitated correctly, drum circles organically employ the spirit of Aloha. Participants actively listen, empathetically respond, create space for others, and develop an understanding of their role in the group. This, too, is Aloha.

Beyond Aloha

Once we have discussed and/or demonstrated the spirit of aloha in the circle, it is now our kuleana to share knowledge of the culture and history of Hawai’i. It is understood that our audience is in attendance to actively participate and to not be lectured, so I recommend creating hand-resting periods to discuss some important cultural and historical points. Many online resources offer inaccurate and sometimes inappropriate information regarding Polynesian cultures, so please be aware if you choose to research and share information. For convenience, I will list various talking points and information below that you may choose to share with your circle.

- Hawai’i can be translated as “breath (ha) across the water (wai).” This can be viewed as the life/love/sharedness across the water, or from another perspective: the creator’s (akua) breath across the water; God/creator/akua shared their breath across the water and provided life to the people.

- Hawaii’s national instrument is both the ukulele and pahu (drum)

- Ukulele should be pronounced as “oo koo lay lay”

- The ukulele is based on the machete, originally introduced by the Portuguese who came to Hawai’i to work in the sugar cane fields.

- Ukulele translates as “jumping flea.” Kanaka Maoli dubbed this instrument the ukulele based on the Portuguese’ playing technique, as their fingers appeared to move like “jumping fleas.”

- The pahu was originally made out of sharkskin along with a wood shell (usually koa or palm). It is reserved more for sacred hula.

- King Kamehameha I conquered and unified the Hawaiian islands and is celebrated annually in Hawai’i on June 11.

- Prior to being taken by the United States, Hawai’i was a kingdom with its own monarchy.

- In 1887, United States businessmen held King David Kalakaua at gunpoint to sign a new constitution that gave away monarchy power, stripped kanaka maoli (Native Hawaiians) of land rights, and gave voting to foreign landowners, thus the term “Bayonet Constitution.” The monarchy was completely overthrown in 1893, the kingdom was annexed by the United States in 1898, and Hawai’i became the 50th U.S. state in 1959.

- Like Aloha, the story of the Bowl of Light is shared with keiki as they are learning about the world of which they are a part. Immediately upon birth, each child has a Bowl of Light. If you tend to your Light, it will grow and you can do all things – swim with mano, fly with ‘iwi, know and understand all things. If you become jealous, envious, negative, or anything that opposes aloha, you drop a stone into your bowl. The stone causes some of the Light to go out because stone and light cannot occupy the same space. If you continue to put stones into your bowl, the Light will go out and you become a stone. A stone does not grow or move. If you tire of being a stone, simply turn your bowl upside down. The stones will fall out and your Light will shine and grow once more.

Adaptable Ipu Heke Rhythms

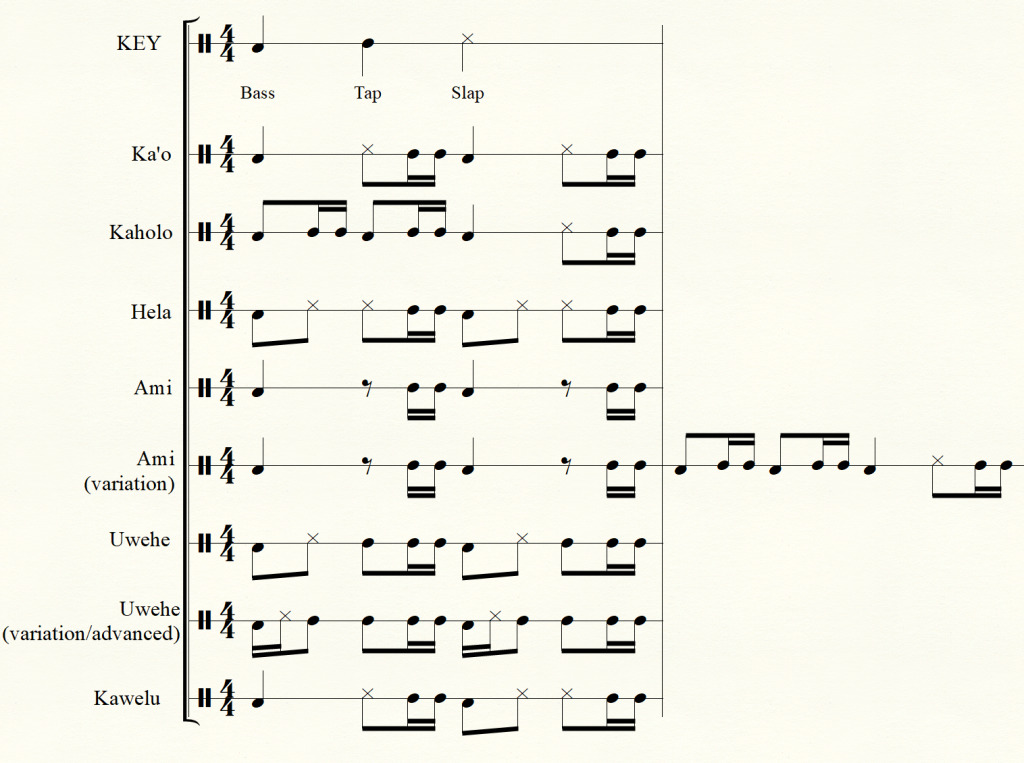

The ipu heke is a double gourd drum used by the kumu that accompanies both hula kahiko (pre-contact hula) and hula ‘auana (post-contact hula). Ipu translates as “gourd” and heke “top.” Thus, a gourd with a gourd on top, or a double gourd. As with most music from across the globe, the rhythms are based on the dance movement. The bass tone (bottom space notation) is created by lifting the ipu and gently striking the bottom of the ipu on the ground covered with a pale (“pah-lay”) which is a soft pad (photo 1). The slap tone (top space notation) is produced by slapping the fingers against the side of the ipu (photo 2) while basic tapping tones (middle line notation) are produced by using the thumb (photo 3) and middle, right, and pinky fingers (photo 4) against the side in a rotating motion, similar to double lateral strokes in marimba performance. The thumb always begins the rotation motion to create the first tap, because it is closer to the kumu and represents the sound coming from within the kumu.

It is important to note that the titles below are fundamental hula steps and not rhythms. The rhythms notated below do not necessarily belong to each hula step; these are simply what I use to teach the fundamental hula steps listed (ka’o, kaholo, hela, ami, kawelu). A hula step does not have its own assigned rhythm that pertains only to it; in each halau, kumu will use their own rhythms for instruction. For example, the rhythm that I use for basic kaholo could be used to teach hela by another kumu.

It is also understood that the facilitator and drum circle members will not have an ipu heke. In fact, I would discourage the use of an ipu heke outside of its context unless the bearer fully understands its role and connection. The rhythms below have had blessing to be shared using more common drum circle instruments (djembes, tubanos, congas, etc.). The bass tone of the ipu could be substituted using the common bass tone for djembe or conga; the tap tones could be performed as standard open tones on djembe or heel-toe tones of conga; and ipu slaps as standard slap tones on djembe or conga. The rhythms may be layered, as in most typical circles, or performed alone as the facilitator chooses. With the understanding of shared cultural respect, they may be performed with rhythms of other cultures at the discretion of the facilitator as long as the circle is taught about their context and spirit of aloha as mentioned above.

Conclusion

I hope this will help you incorporate true Aloha into your next drum circle. It is now your kuleana to share this information in a respectful manner to help better strengthen global citizenship and intercultural understanding among members of your drum circle. I am always available as a resource and happy to help with collaboration, clinics, lectures, workshops, etc. so please do not hesitate to reach out. Happy drumming and much aloha to you!

—-

Percussionist, educator, composer, and ethnomusicologist Jeremy Kirk is Associate Professor of Music at Southwestern College (Winfield, KS). Recipient of the Southwestern College Exemplary Professor of the Year Award, Kirk is deeply committed to providing students the skills necessary to excel in today’s world as an educator, performer, and global citizen. Highly regarded and in demand for his expertise in arts and culture of Polynesia, he combines his traditional training in Western percussion with his extensive knowledge in world music to create a unique global perspective in his teaching and performing. Kirk is an artist and clinician with Majestic Percussion, Mapex Drums, Vic Firth Sticks & Mallets, Sabian Cymbals, Remo Drumheads & World Percussion, and Black Swamp Percussion. To connect with and learn more about Kirk, please visit www.jkpercussion.com.

This article was originally published in Percussive Notes in June 2024