By Dr. Phillip Payne, Assistant Professor, K-State University

Teachers encountered a dramatic shift in instructional delivery, student interactions, and professional responsibilities with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in the spring of 2020. Teaching classes swiftly moved from in-person to virtual in the matter of a single week, student interactions became reduced to 2×2 squares on a computer screen, and checking in on the mental and physical wellness of our students became an integral part of our daily protocols. Within days of the onset of the pandemic, Gov. Laura Kelly announced that schools would not reopen for the 2019-2020 school year – starting a trend that would expand nationwide, resulting in nationwide lockdowns/quarantines.

COVID-19 required teachers to creatively revise learning plans and structures on short notice while maintaining students’ motivation while covering as much information as possible given the circumstances. Furthermore, teachers had to consider the academic load and the learning expectations since most current students and teachers had never experienced fully integrated remote learning. Internet access, usable technology, and time on task all had to be modified according to the current environment. This posed both challenges and opportunities as classrooms that had previously been operating face-to-face moved to virtual or hybrid.

Prior to the pandemic, music educators had limited exposure or experience in remote instruction. Due to a domino effect of school district closures in March 2020, teachers had to quickly identify and develop effective strategies to teach their students at the start of lockdown. This massive shift in modality proved to be a challenge, especially limited in-person contact and complete asynchronous instruction. Given the participatory nature of music education, asynchronous work meant that lesson design and content had to be modified almost entirely. Before the pandemic, performance was a central element; however, the cancellation of all public events during the quarantine changed the priorities and possibilities of music teachers. An additional shift in teaching modalities occurred with the onset of the 2020-2021 academic year. School districts began designing remote and hybrid options during the summer months in preparation for Fall 2020. This shift included implementing substantial curricular modifications while adapting to the technological, emotional, economic, and social needs of every student.

As the COVID-19 infection surge subsided and experts recommended a return to the classroom, the districts developed individual policies for face-to-face classrooms, which required adherence to new strict safety regulations. This included but was not limited to the use of face masks, social distancing 6 feet, bell covers for wind instruments, and classroom ventilation procedures. Facing this new reality, each teacher had to not only adjust to the requirements of their district but had to begin reframing how they taught both in scope and approach. Reading a room of masked faces was radically different from a normal classroom, especially during a music rehearsal. Effectively rehearsing an ensemble with masks and bell covers required more specific and nuanced skill sets than previously required. Such changes did not represent a return to normalcy but reflected an echo of remote learning seeping into the physical classroom.

Unlike previous pandemics, advancements in technology over the last century allowed for education to continue uninterrupted through the lockdown. Su and Guo (2021) shared that “In light of the sudden effects of the COVID 19 outbreak, we recognized that students must use the platform and tools provided by their school to perform a thorough online learning program at home, review the teaching material prepared by teachers, and partake in online conversations or exchanges with teachers and students.” Public schools met these expectations and achieved this feat by establishing a framework for remote learning in public school settings. Students, teachers, and administrators relied upon various video-conference platforms (i.e. Skype, ZOOM, and Google Meets) and learning management systems (i.e. Canvas, Blackboard, Desire 2 Learn, and Google Classroom) to serve as a foundation for maintaining some connection to the students and “normalcy” within the virtual classroom.

The COVID-19 pandemic forced educators to re-think and re-frame their teaching methods and pedagogies, especially as educational institutions switched to online learning. Implementing such massive shifts in such a short window while impacting normalcy within all stakeholders has created a sense of imbalance both professionally and mentally. With a mounting set of literature developing prior to the pandemic on mental health and self-care, the pandemic shed light on an already growing issue in the education profession.

This research sought to understand how Kansas music educators perceived their mental health and general well-being as schools returned to in-person and hybrid instruction after lockdowns. Therefore, the primary goal of this study is to reveal any shifts in attitudes, beliefs, or perceptions of current music educators as they relate to instruction, classroom environment, mental well-being, and the teaching profession following the spring of 2020. Our purpose is encapsulated within the following research questions:

Research Questions

- What perceptions exist among music teachers regarding their own health?

- Are there any differences in these perceptions from pre-2020 to return to in-person instruction?

- What are Kansas music teachers’ perceptions of students’ interaction with the school environment throughout the pandemic?

- How has the pandemic altered classroom instruction, daily activities, and learning community expectations and obligations within music education?

Method

Instrument

We administered a researcher-generated questionnaire for the current study. The researchers piloted the initial edition with music educators to ensure clarity of questions and proper data collection to assist in answering the current research questions. Once revised, the questionnaire comprised a combination of 19 multiple choice, Likert scale, and fill-in-the-blank questions aimed to comprehensively address the primary focus of the study. We prompted teachers to share their perceptions in three areas: (a) overall health, (b) student interactions, and (c) perceptions of educational technology as they existed for pre-COVID during the lockdown and their return to the classroom. Additional questions focused on the availability of support for mental health services for their classroom community and how the lockdown has generally impacted their music education programs.

Procedures

Following approval from the Kansas State University Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the Kansas Music Educator Association (KMEA) Executive Board, the webmaster for KMEA sent 1988 emails on March 23, 2022, to current music educators and members of KMEA and a follow-up reminder approximately 7 days later: March 30, 2022.

We designed and administered the survey using Qualtrics Survey Software. Given the small scope of the study and regional focus, we masked all IP addresses and did not collect specific school information to maintain anonymity and allow for full transparency and honesty by the respondents. Furthermore, we employed the “Prevent Ballot Box Stuffing” feature in Qualtrics to guard against multiple entries by the same members. Given the proclivity to be more honest about difficult subjects when answering anonymously, we felt this represented the best way to collect the data. Upon closing of the survey on April 8, 2022, we downloaded and organized all data using MS Excel. Through Excel and Qualtrics, we successfully developed a demographic snapshot of the respondents and began to reveal the perceptions of Kansas music educators as it related to all aspects of the pandemic. We employed measures of central tendency, frequencies, linear correlations, and paired-samples t tests to fully answer each research question. Results are provided below with an extensive discussion of our profession and reactions to a return to in-person instruction following the lockdown of Spring 2020.

Results

Participants

Participants (n = 135) comprised music teachers from across the state of Kansas. Most music educators identified as female (55.7%) and provided an average age of 41.81 years (SD = 12.31). (Given a range of 49 years, the large standard deviation indicates a broad range of respondents with a majority of the respondents falling below the mean.) Respondents indicated an average of 16.92 years of teaching, with all but 1 teaching in Kansas. (There is one respondent who kept their KMEA membership active while moving out of state.) The survey reached teachers of all areas, including band (36.87%), choir (24.88%), general (31.34%), and orchestra (6.91%%). A majority of respondents shared that they taught in secondary schools (63.92%), with elementary (29.11%) and post-secondary (6.96%) representing smaller sections. Finally, music teachers who responded accounted for a cross-section of locales (Urban – 20.89%, Suburban – 41.4 %, Rural 37.97%) with a strong lean toward public institutions (93.04%). See Table 1 for a full demographic breakdown of the respondents.

Music Teachers’ Perceptions of Their Health

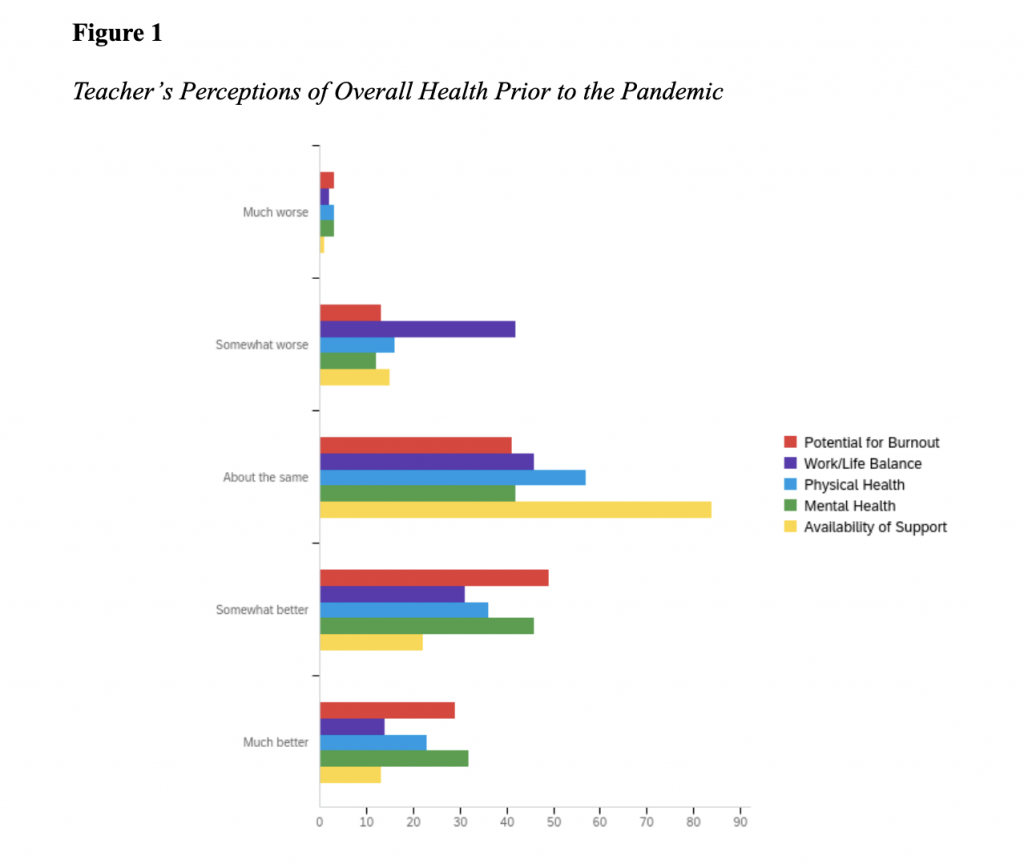

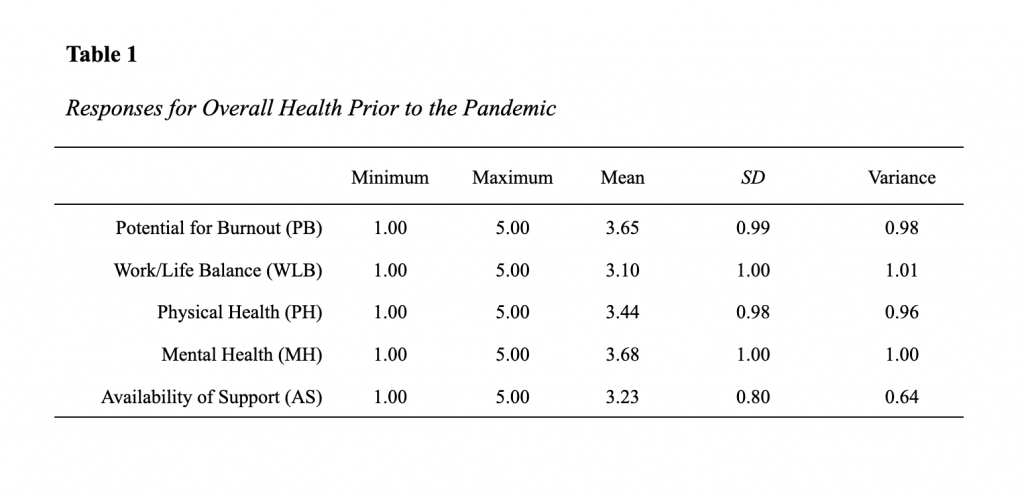

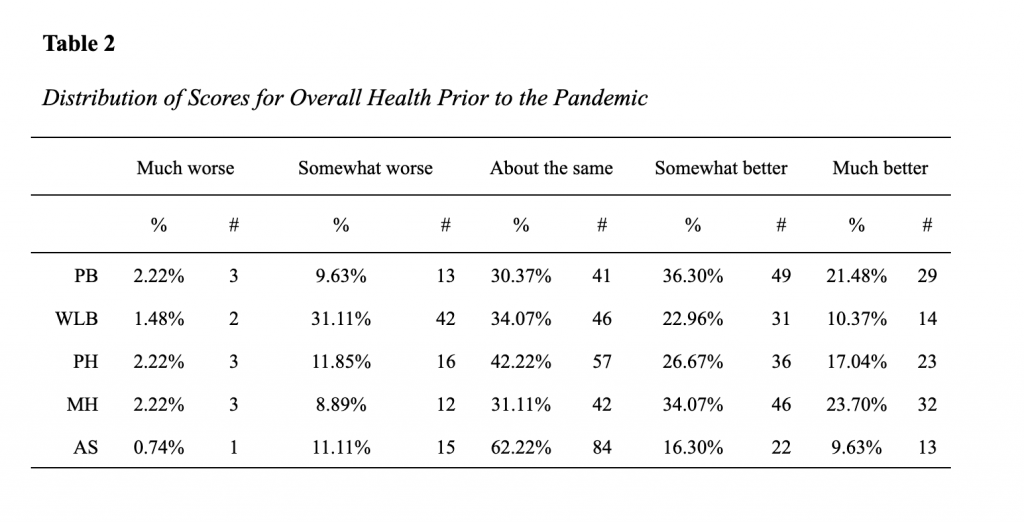

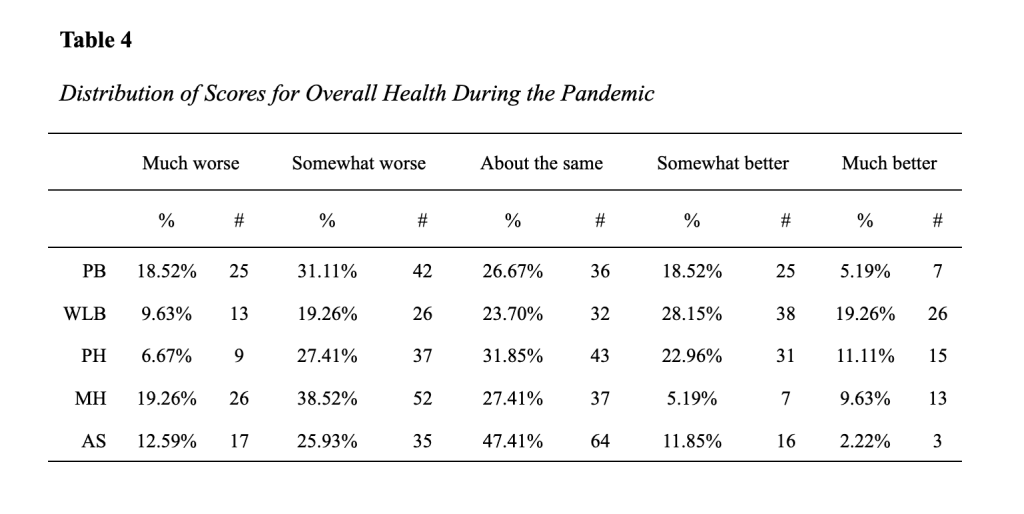

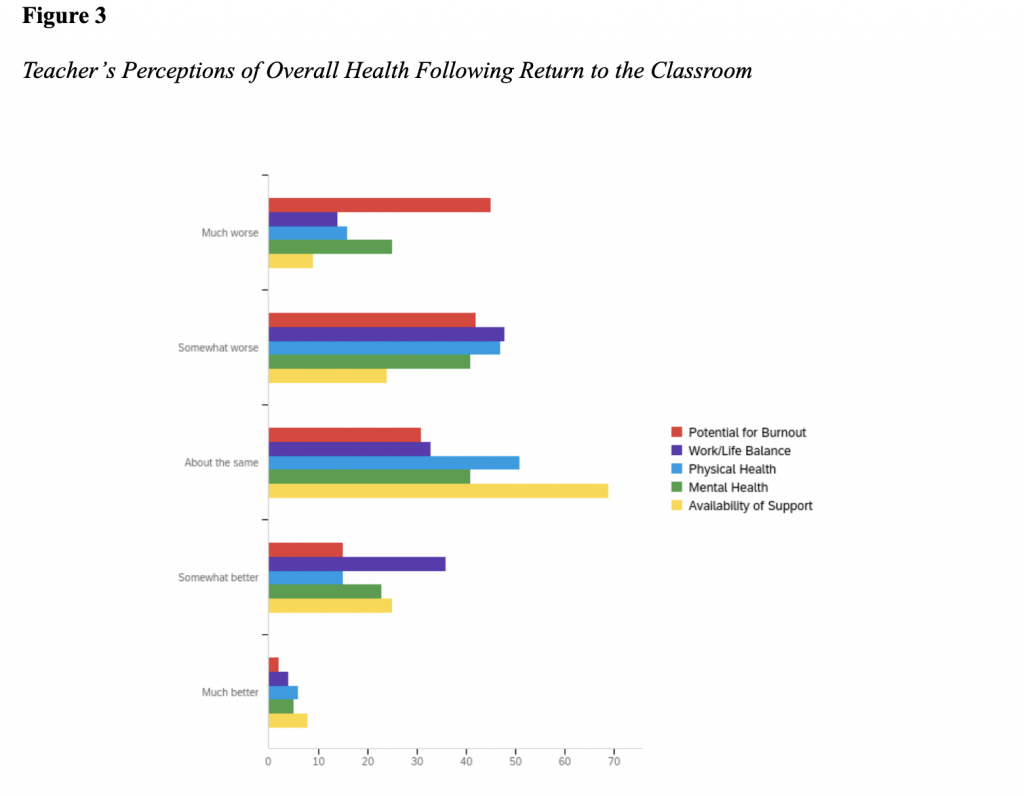

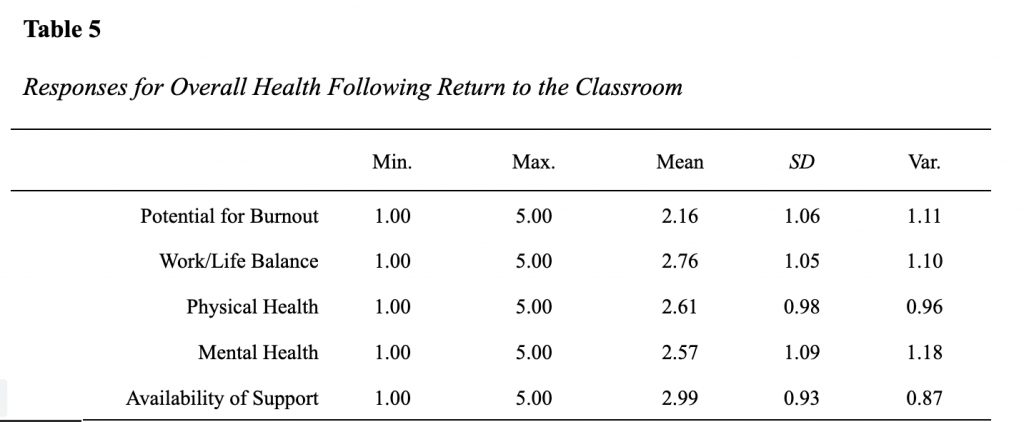

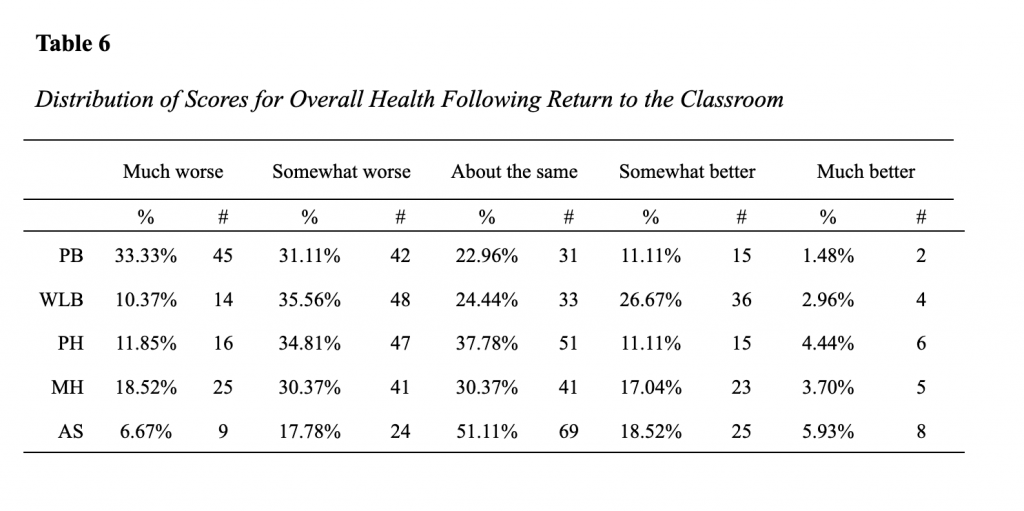

Teachers reported their perceptions of overall health in three distinct periods: (a) prior to COVID, (b) during the lockdown, and (c) after returning to the classroom. The following data represent these perceptions in five distinct categories: (1) Potential for Burnout, (2) Work/Life Balance, (3) Physical Health, (4) Mental Health, and (5) Availability of Support. Each teacher responded on a scale of 1-5, with one representing Much Worse and 5 representing much better as it related to these areas given the specific time frame.

Prior to COVID, Kansas music teachers perceived their overall health in decent terms. The only issue that appeared to arise seemed to be Work/Life Balance and the struggles associated with teaching music, and the time required outside of the school day. Otherwise, most teachers reported that their health in other areas remained about the same or better in every category. (See Table 1-2 for more specific information.)

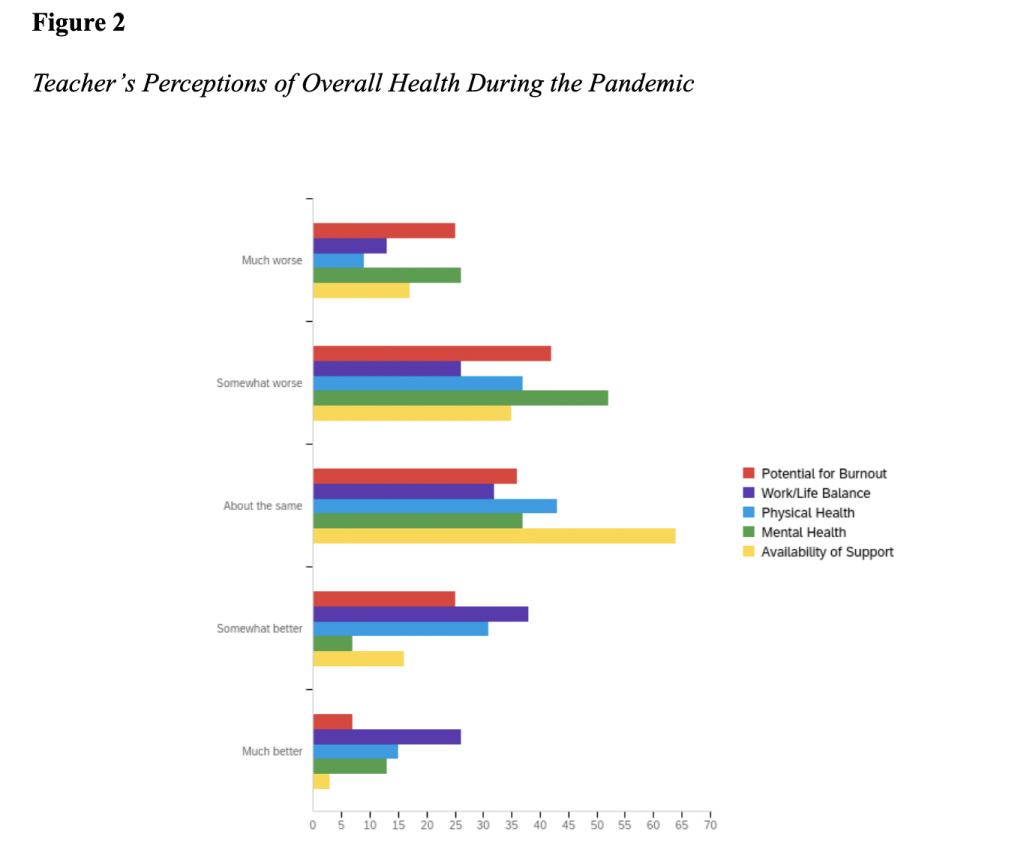

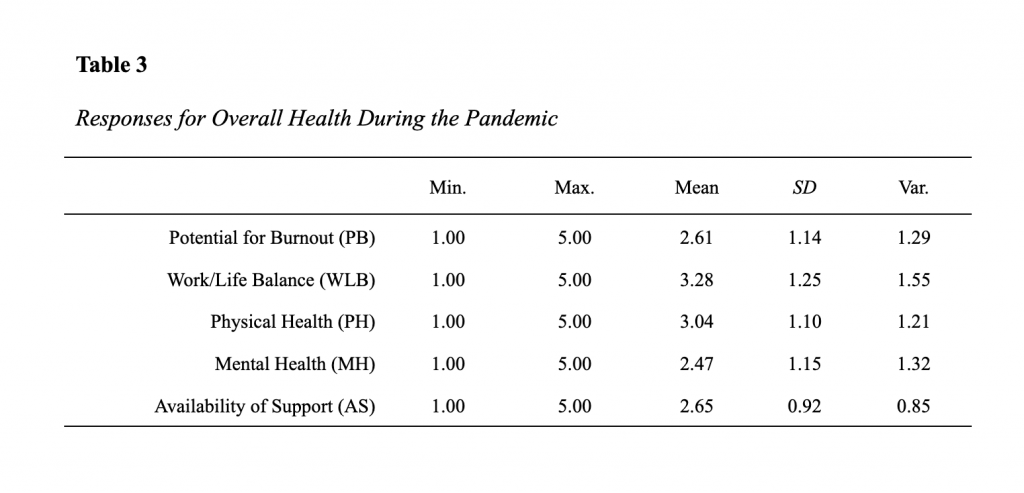

An observable shift emerged in the spring of 2020 as the move to lockdown status occurred. Teachers report that the potential for burnout increased as the lockdown began. They also shared that their mental health and availability of support plummeted during these months. Conversely, we observed an increase in their ability to handle the work/life balance according to their perceptions. (See Table 3-4 for more specific information.)

Finally, as the teachers returned to the classroom, they reported that the potential for burnout continued to increase and became much more of an issue. Work-life balance once again plummeted to lower than prior to the pandemic, and mental health continued to suffer in their own perceptions. While the availability of support appears to increase following the return to the classroom, it still does not attain or exceed pre-pandemic levels. (See Table 5-6 for more specific information.)

Across all levels, we see the negative impacts on Kansas music educators regarding their perceptions of their health. The threat of burnout has significantly increased, work-life balance appears to have fallen below pre-pandemic levels, all while physical and mental health are paying the price for this return to the classroom. Support continues to wane and is not yet back to pre-pandemic levels. In each of these experiences, we see that teachers are surviving, but have yet to figure out the process of thriving in this new environment and set of processes. In our own experiences, we know this is happening; however, to see it documented brings this issue to life.

Given these facts, the researchers inquired as to whether these changes from pandemic to now were significant. After a paired-samples t test, data indicated that these differences were all significant from pre-pandemic to present. The perception of potential burnout reported post-pandemic was significantly higher than prior to Covid-19. Music teachers’ perceptions of their mental health revealed a significant decline over the past two years, and this is expanding into the perception of their physical health, which also revealed a significantly lower perception. In all areas, the researchers found significant changes within the music faculty, indicating an increased possibility for burnout, lower physical and mental health, and an ability to maintain a healthy work-life balance. These must be examined further to truly determine the impact of these findings.

Perceptions of Students

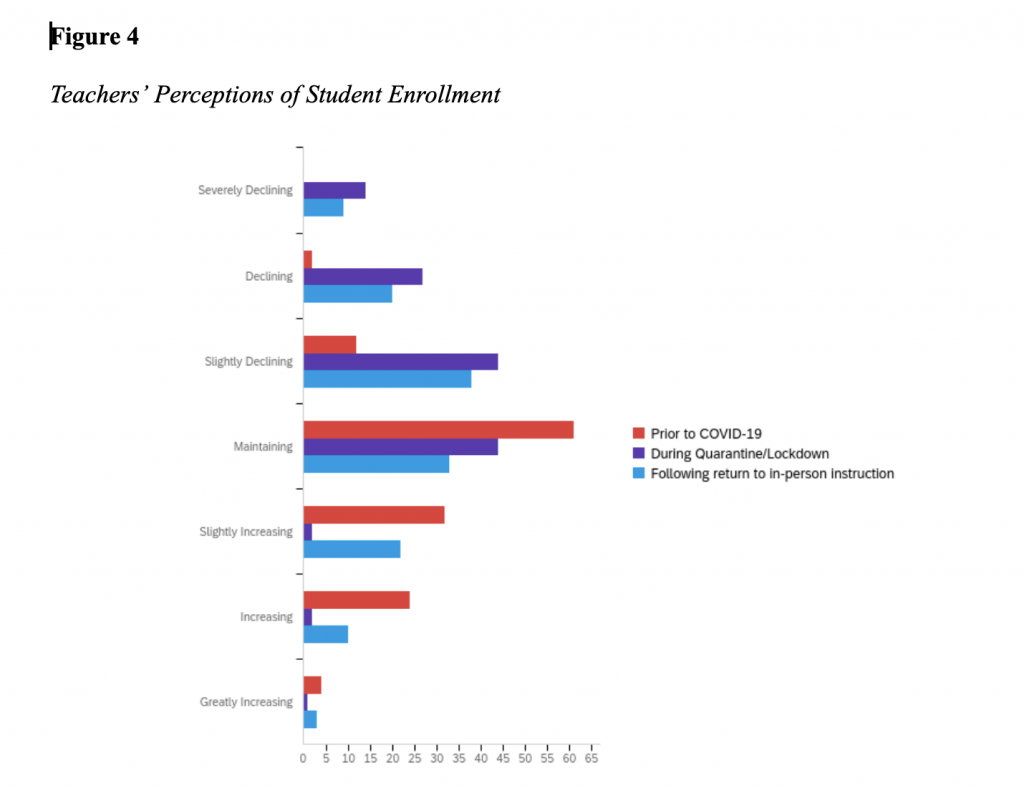

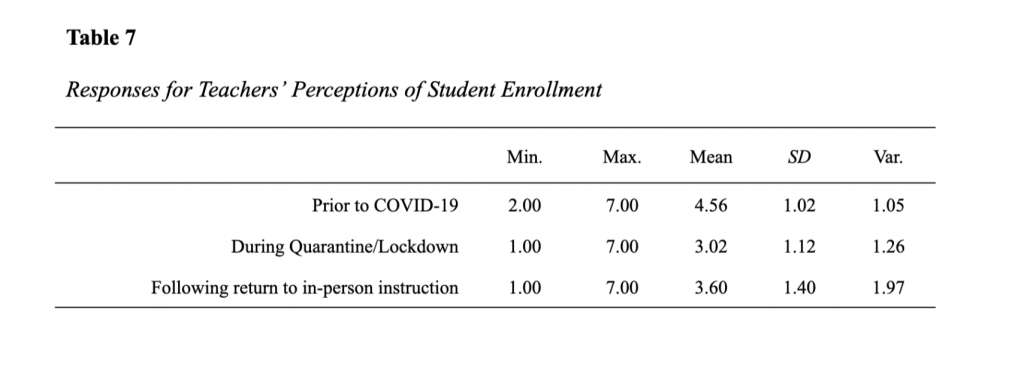

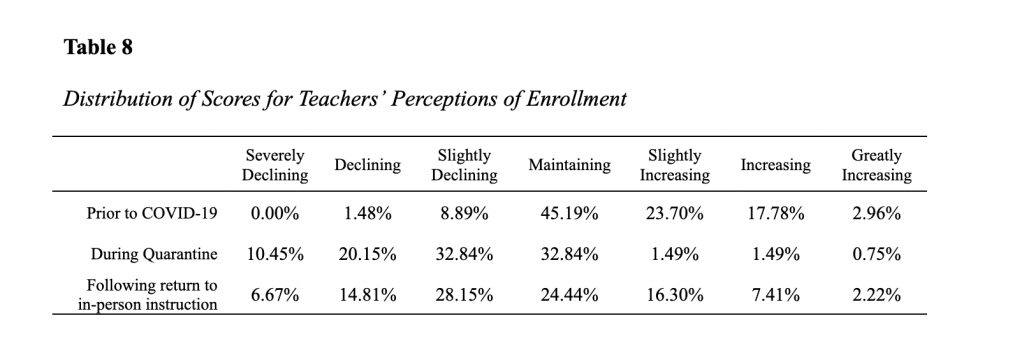

Enrollment remains a primary issue facing music educators post-pandemic. Many (45.2%) of music educators shared prior to the pandemic that they had increasing enrollments, with an overwhelming majority (89.6%) indicating a sense of maintaining enrollment throughout their programs. However, following the onset of the lockdown and the ensuing multiple approaches aimed to ensure the safest learning environments for students upon their return, enrollment is emerging as a primary issue. A majority (63.5%) began seeing enrollments decrease during the pandemic. This trend downward continues but begins to level off upon return to the classroom. While students are returning to the programs they once populated, the initial numbers are not back to pre-pandemic levels (See Table 7-8). Additional years of data will be necessary to truly see the impact and recovery of music education in the state of Kansas.

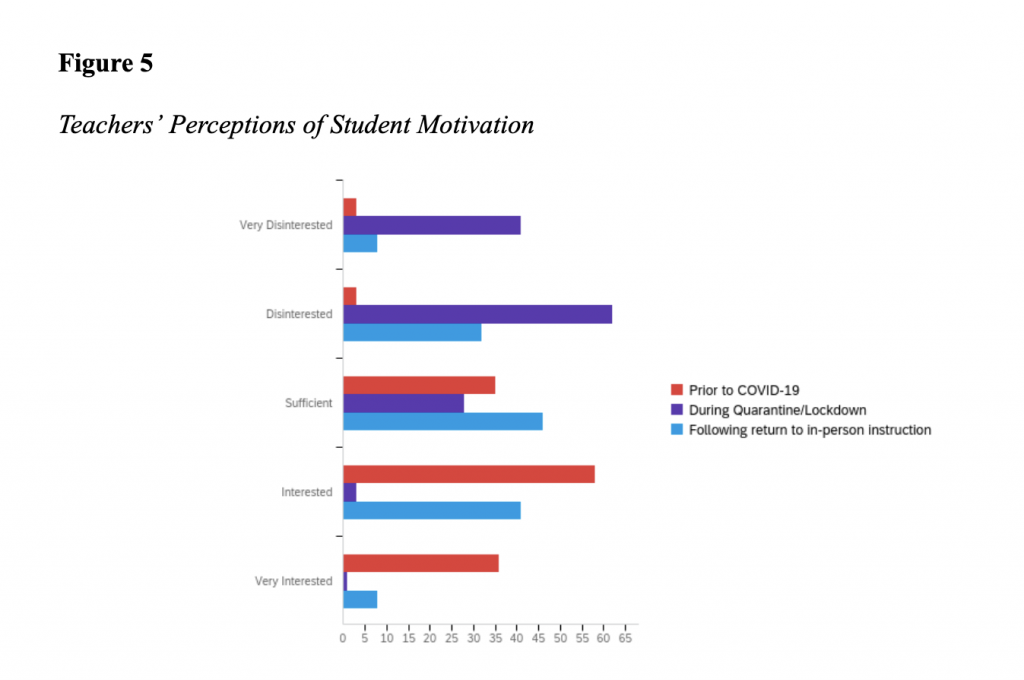

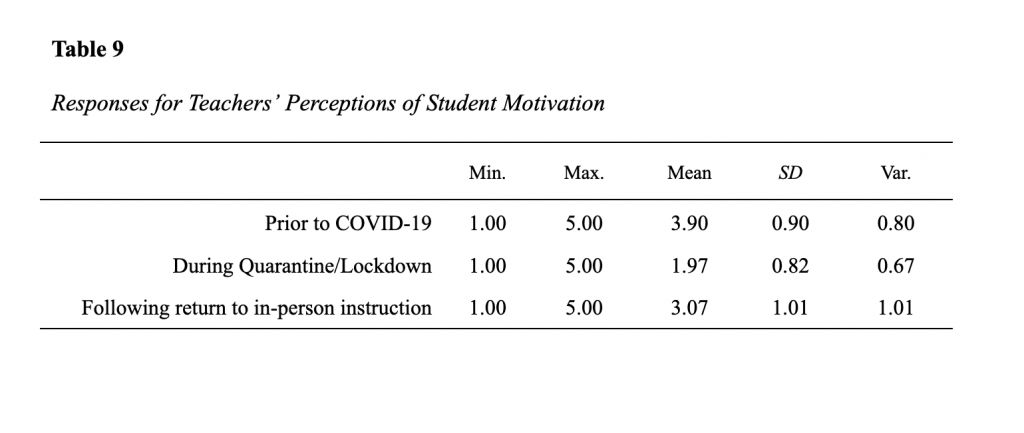

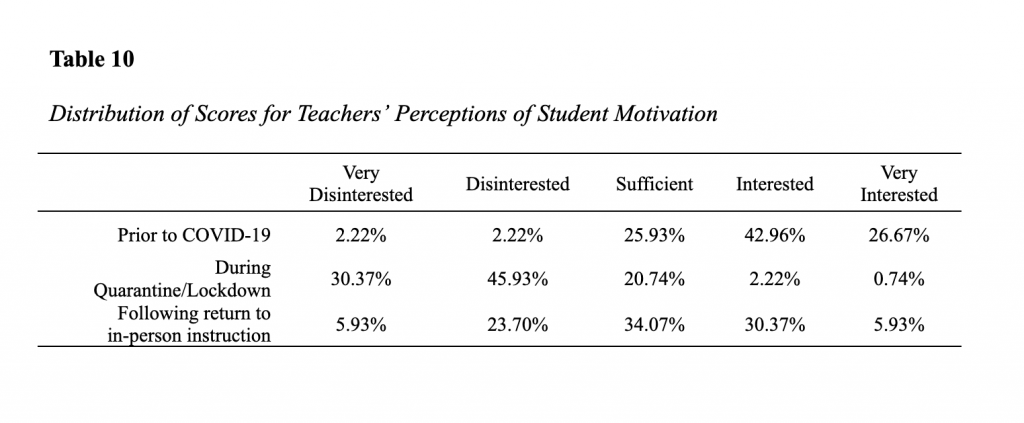

Another area the researchers explored included motivation. Kansas music educators (56.2%) shared that students lost a great deal of motivation for practice and participation in music classes over the course of lockdown and return to the classroom. Similar to the enrollment numbers, while students seem to be recovering regarding their motivation to practice and participate in music, they have not recovered to the baseline established in the pre-COVID era (See Table 9-10).

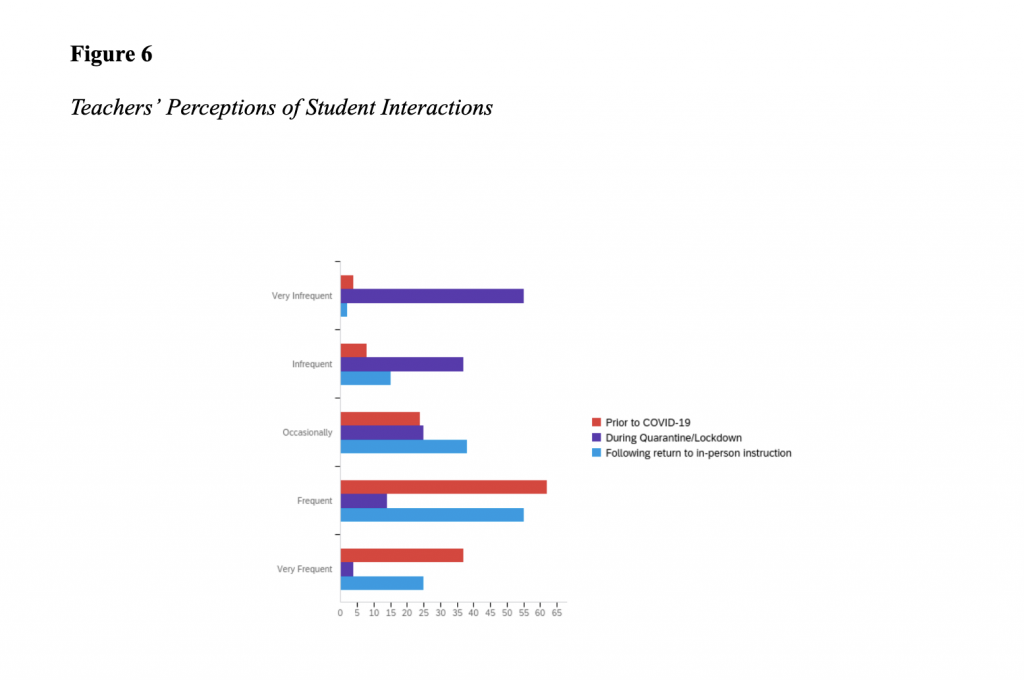

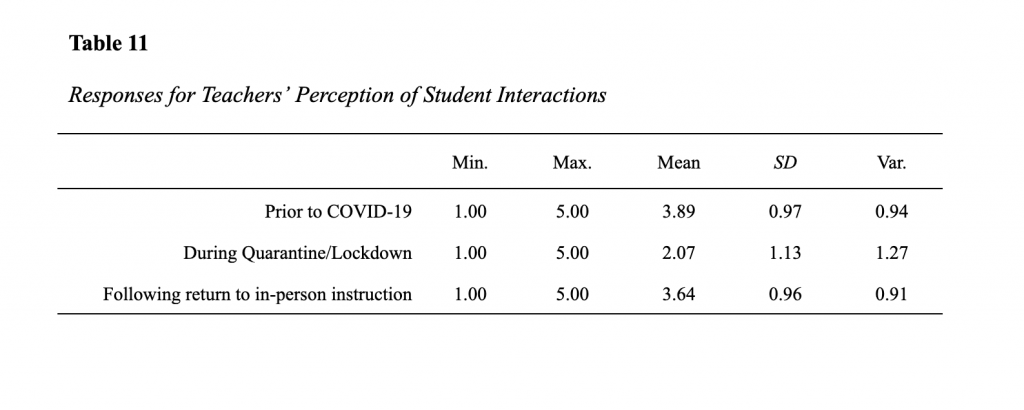

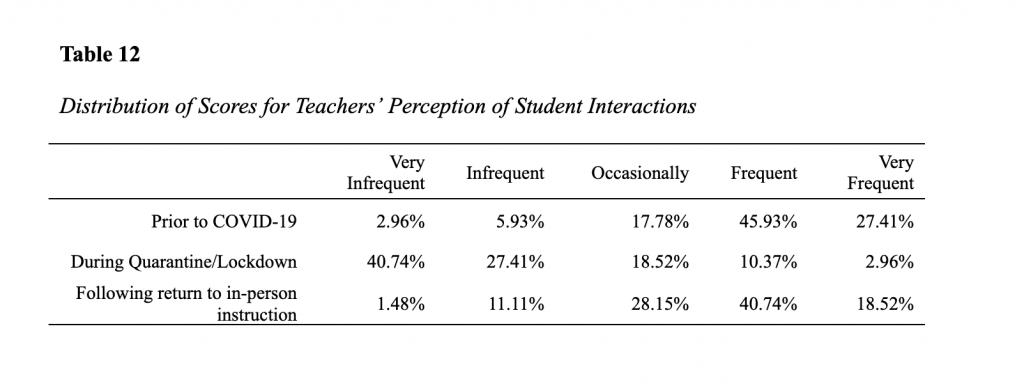

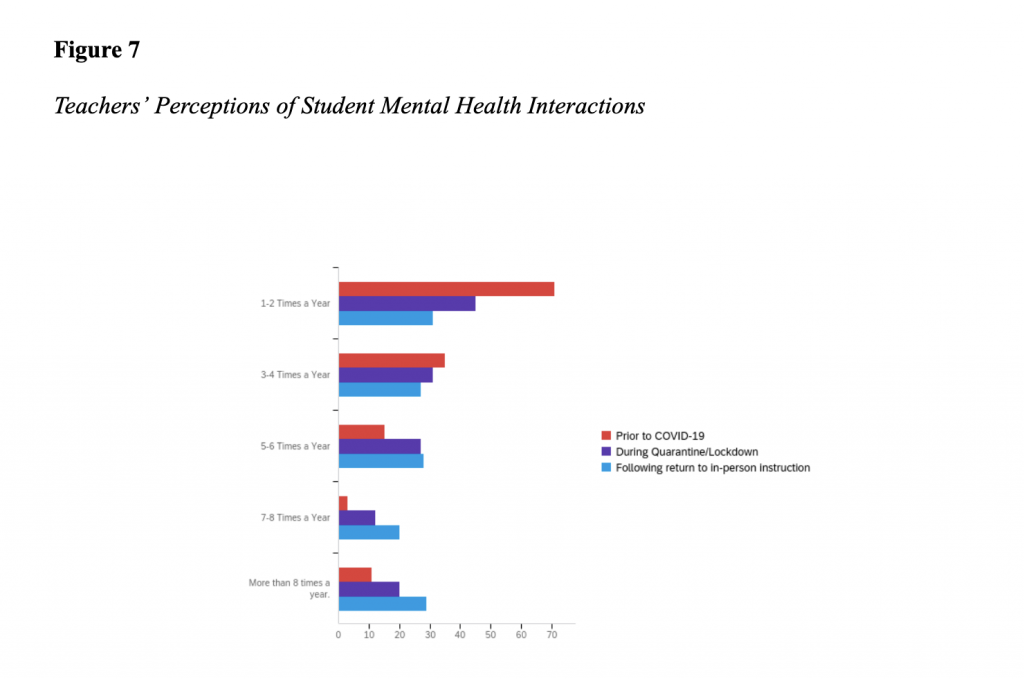

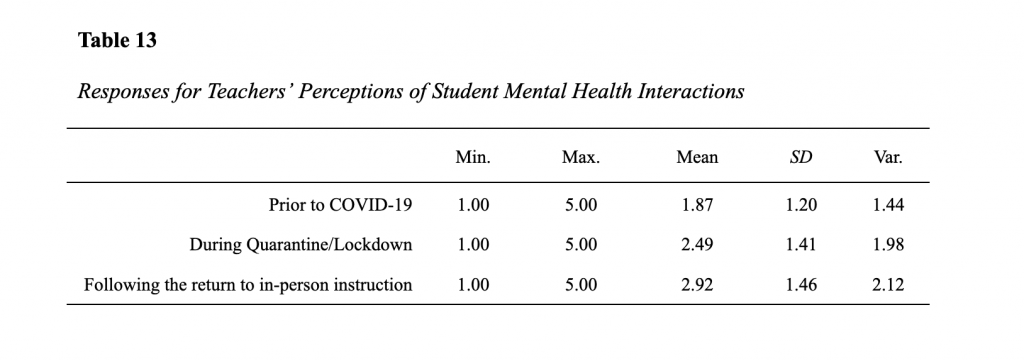

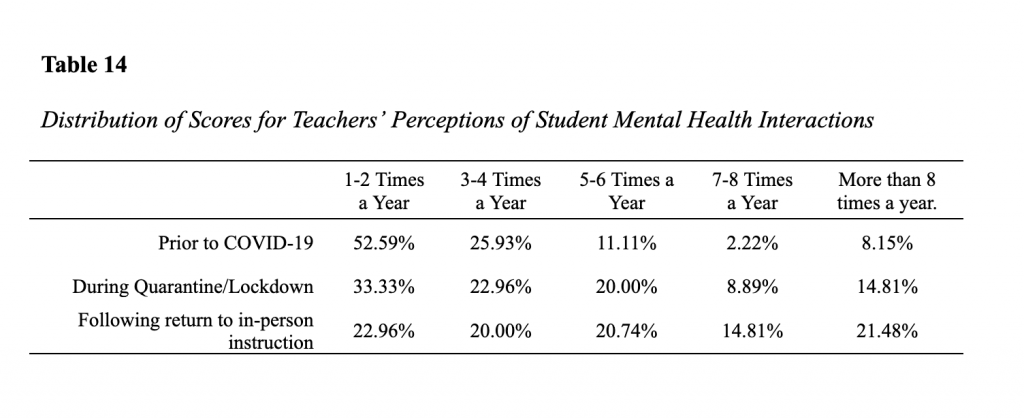

One area the researchers asked specifically about were interactions with students, specifically any that dealt specifically with mental health issues. While most teachers reported that their individual interactions bottomed out during the pandemic due to lack of access, they also shared that they have almost returned to pre-pandemic levels. However, the researchers found a significant rise in the number of interactions with students dealing specifically with mental health. Where teachers most frequently addressed this issue 1-2 times a year prior to COVID-19, they are now addressing mental health crises for students 7+ times a year following the return to the classroom (See Table 11-14).

Perceptions of Online Learning

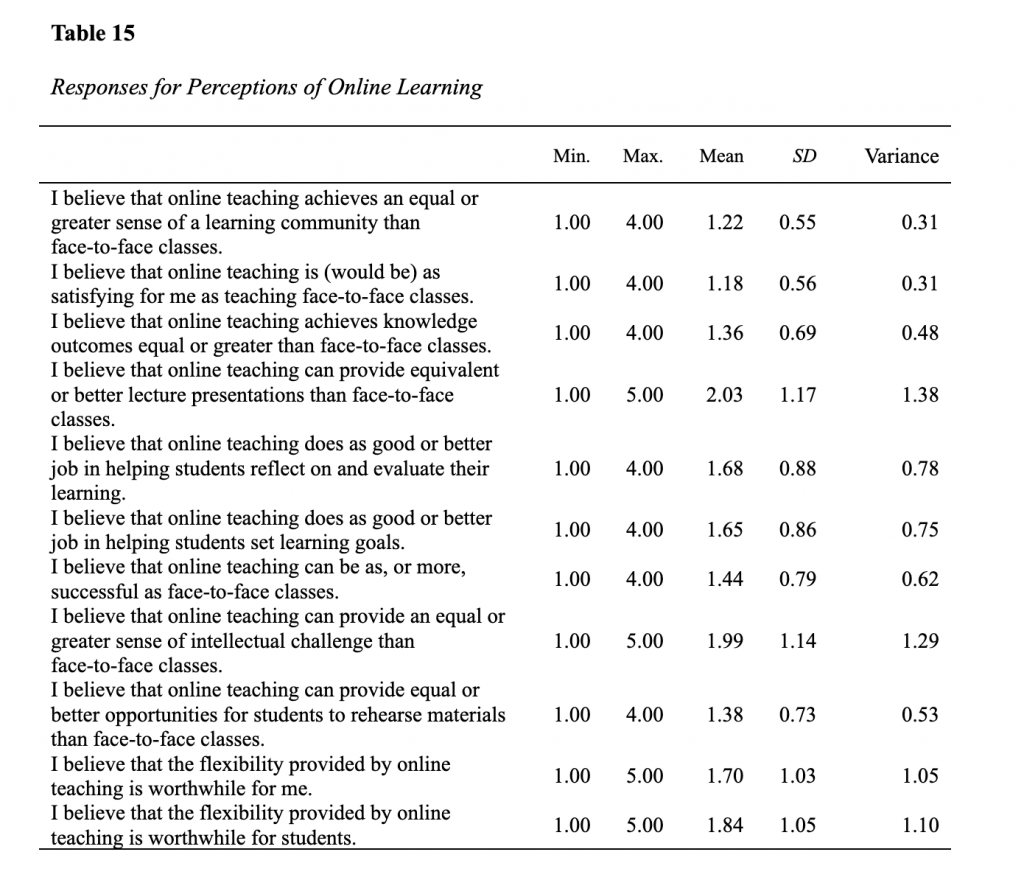

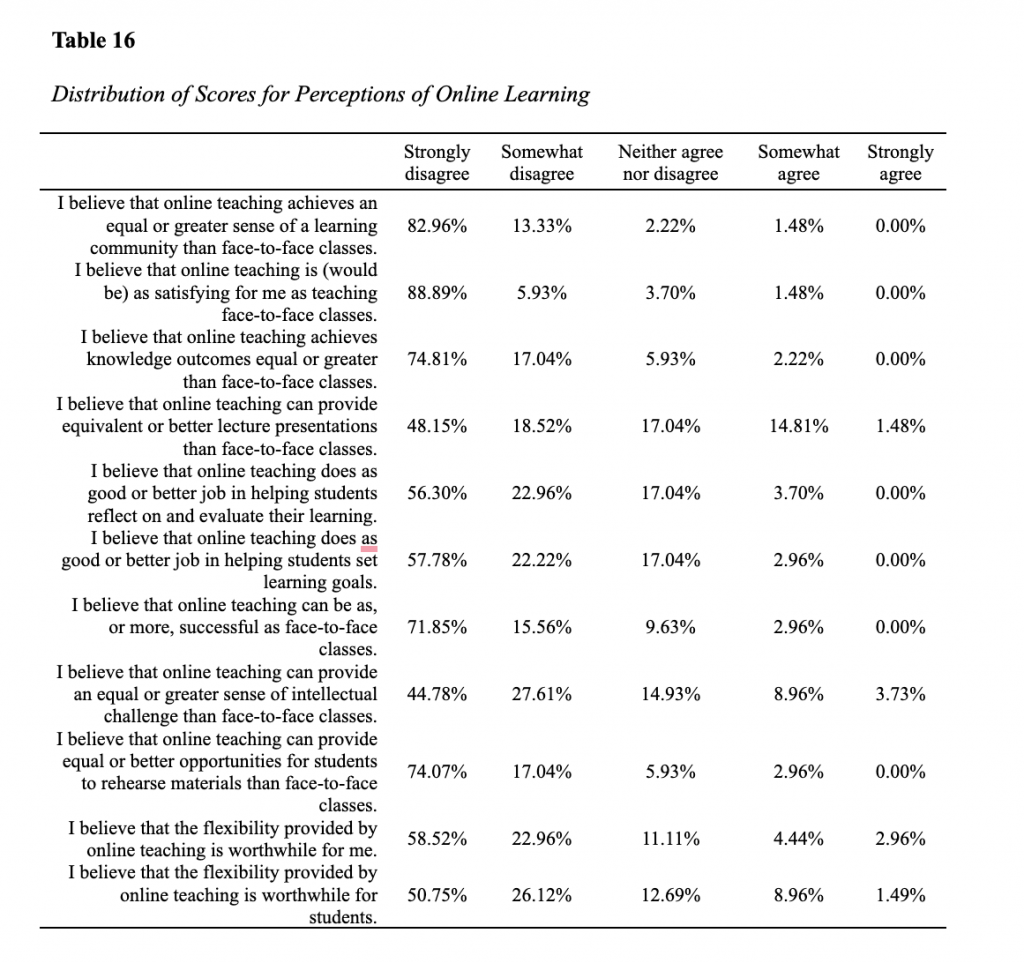

Overall, Kansas music teachers report that they do not see the value of online teaching. They question its ability to create learning communities, they frequently end lessons dissatisfied with the product, they do not believe students develop the same reflective skills, and they do not see it establishing an environment that is conducive to the most effective learning. Kansas music educators consistently held these beliefs when posed with the same questions. However, they also varied on some issues as they related to online learning. They varied widely regarding the efficacy of online delivery for lectures, virtual learning as a means to sufficiently challenge students, and the level of flexibility that online learning provides to the students and the teachers (See Table 15-16). In essence, Kansas music educators want to be back in the classroom but also are seeing some value in the use of technology within the current paradigm.

Discussion

Music educators may live in different communities across the state of Kansas, but they have experienced similar feelings of concern and frustration across a variety of topics. Our focus in this study aimed to answer three primary questions (1) What perceptions exist among music teachers regarding their own health? (2) What are Kansas music teachers’ perceptions of students’ interaction with the school environment throughout the pandemic? And (3) How has the pandemic altered classroom instruction, daily activities, and learning community expectations and obligations within music education? In each case, we found a baseline to begin discussions and advocacy for our music educators moving forward.

Question 1 addressed the perceptions of mental health of our Kansas music educators. Kansas music educators are tired and trending toward severe burnout. Understanding this pathway at a deeper level and focusing our advocacy toward their support with administration and the profession will be critical. Additional research needs to occur to address the underlying issues that are the source of this burnout. One possibility is that the pandemic revealed many of the issues that were lying just beneath the surface of our profession. Work-life balance is a primary topic that we see improve during the lockdown and plummet in the return to the classroom. It goes below pre-pandemic perceptions because of the added layers of stress that teachers are feeling on a day-to-day basis. Providing support for teachers to address this issue will be paramount for our association as we continue to navigate the years following the return to the classroom.

Burnout and mental health will initially be viewed as outgrowths of the pandemic, but these issues existed previously but were often downplayed or not provided sufficient attention. These factors can no longer be ignored. Building on the works of Bernhard, Payne, Kuebel, Allen, and many others who have researched burnout, mental health, and self-care and their role in the life of a music educator, we must not assume that a return to the classroom will solve the issues revealed by the pandemic. COVID-19 only pulled the covering away from these issues rather than serving as the launch point for these topics. There cannot be a return to normal, but a hard look at how we move forward as a profession. Just in this survey, we see the impact and potential pitfalls that lie ahead.

Question 2 addressed the interactions of teachers and students pre and post-lockdown. The data reveal that while positive interactions are rebounding with a return to the classroom, the stress and impact of COVID-19 is also felt with the increase of interactions focused solely on mental health. This is important for the profession in that support cannot be only focused on the teachers, but the students as well. Advocating for all involved will be critical in our next steps. Sharing this information with administrators and stakeholders will help share the story that while we are getting close to where we were pre-pandemic in terms of statistics, we are in a different place socially, emotionally, and musically. This part must be communicated and stressed within all our interactions.

Question 3 focused on differences of approach. While the pandemic did not alter the approach outside of the lockdown and initial return, the practices and interactions we have will maintain a residual effect for years to come. We saw this in the variability within how to implement lessons learned with virtual/remote learning. There were some positives, but the overwhelming urge to return to the classroom lowered the possible impact because of its connection with the pandemic and overall perception that it just isn’t as good. The researchers felt that the perceptions and evidence revealed in this study could open the door to conversations about how we approach music education and ways that we can use lessons learned from this experience to expand and enhance music education across the state.

Final Thoughts

Music educators throughout the pandemic were not only teaching their students but learning simultaneously. Their ability to be flexible and adapt allowed for the pandemic to bring more technological savvy to both music educators and students alike. For instance, many teachers established a “live streaming” of concerts to showcase student work and have continued this connection and creation of access to the program post-pandemic. Collaboration and interdisciplinary activities are other emerging trends among our music teachers. Connections that would have been difficult during pre-pandemic structures were now more easily accessible. While these bright spots do not erase the impact of COVID-19 they do reveal that we have opportunities to grow music education and connect with a wider audience. We must start this next portion of our journey by first addressing our own health and wellness as music educators. Our next steps must be to look into the positives and negatives resulting deeply and objectively from the pandemic. Finally, we must use this data to vigorously advocate for our students, teachers, and programs to all administrators, communities, and stakeholders to ensure that we continue the positive impact that music education has on our students in the years to come. We should not forget the experiences, lessons learned, and the opportunities for growth afforded to us during this period of time for music education in Kansas.

Referencese

Su, C. & Guo, Y. (2021). Factors impacting university students’ online learning experiences during the COVID-19 epidemic.