By NAfME Member Michaela Johnson | reprinted with permission from Music in a Minuet national NAfME blog |

Dear Music Educator,

Are you aware of the string teacher shortage in the United States? Across the country, string programs are having difficulties finding qualified educators, sometimes even resulting in canceled string programs. In the rural community where I was raised, the closest string program was an hour away. Dr. Angela Ammerman, the music education professor at the university I attended in my hometown, was constantly encouraging the music education majors—none of whom played a string instrument—to consider teaching strings or even starting their own string programs because she recognized this stark lack of string programs in our community. If you, like me, are a non-string music educator, perhaps you weren’t previously aware of this shortage. However, now that you are aware, I challenge you to ask yourself if there is anything you can do to combat this issue.

Sincerely,

A lifelong trumpet player turned violin teacher

Beginnings

In this blog post, I offer a solution to the string teacher shortage and my personal story as proof of this solution’s validity. Although there could be many potential solutions, what I believe to be the most trustworthy and immediate option is training current non-string music educators to transfer their musical knowledge and experience of band, choir, or general music into the string world. After all, non-string music educators already have a degree, a teaching license, and a passion for music education.

Why would a non-string educator want to transition into the string world?

Making the transition into the string world would be beneficial to both you and your community, especially if your community does not already have a string educator. Not only will you gain more teaching experience and make yourself more marketable in the job force, but your community and future students will also gain a new resource for string education.

What would it look like if current non-string music educators were encouraged to accept string positions, if those positions could not be filled by existing string-specific educators?

As I fall into the category of non-string educator turned string educator, I will now offer my personal story as proof that non-string educators can and should be entrusted to teach strings.

My Journey

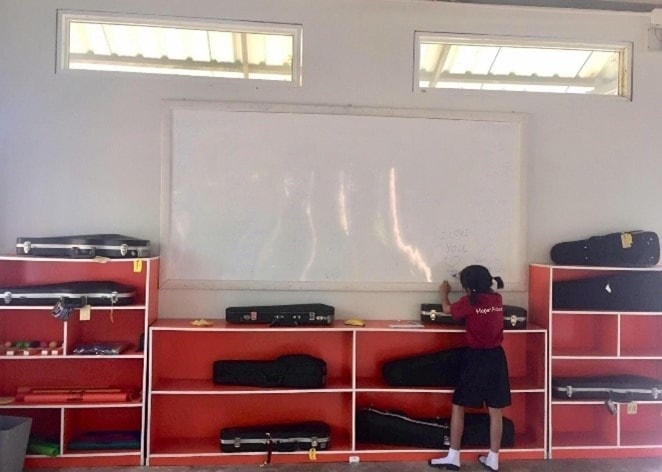

My journey to becoming a violin teacher started when Dr. Ammerman encouraged my classmates and me to accept an opportunity to teach strings if we came across an unfilled position. My string journey continued when an opportunity finally presented itself: teaching at the Hope House Children’s Home in Chiang Mai, Thailand, where Dr. Ammerman had recently started a string program. After more than a decade of playing the trumpet and then earning a music education degree from the University of Tennessee at Martin, I began teaching violin 8,500 miles away from my hometown. I had to fully embrace this opportunity, learn to play the violin, and overcome various internal and external struggles that I never could have predicted.

The first and most important lesson I learned through my experience teaching strings was how to play the violin. Dr. Ammerman gave me a few private lessons, and then I practiced independently for roughly half a year before starting my teaching position at Hope House. Even more difficult than learning to play the violin, I discovered once I started teaching that I would also have to learn to play without obsessively watching my hands. As a beginner violinist, I relied on these visual cues while playing. I quickly realized my dependence on visual cues would hinder me, as the teacher, because it became more imperative for me to watch and assess my students’ hands rather than my own.

In addition to learning how to play the violin, I was also challenged by the task of teaching music concepts to students who spoke a different language. Not only did I speak a different language than my students, but many of my students spoke different tribal-specific languages than each other, such as languages used in the Akha, Lahu, Karen, Hmong, and Lisu tribes. For a vast majority of my students, Thai was their second language, and English was their third language. Thankfully, music is a particularly unique subject to teach to students who speak different languages because many music concepts can be communicated through modeling and visual examples as opposed to verbal explanations. Because verbal explanations are not always necessary when teaching certain music concepts, people who do not speak the same language can still learn from one another despite the language barrier.

The students at Hope House were no exception: they were able to learn many musical concepts, including music literacy, with minimal verbal explanations. In fact, once they were able to read music notation, we had a common language that we could all use to communicate. This challenge of learning how to work with students of different cultural and language backgrounds turned out to be one of the most beneficial learning experiences of the entire journey. Because of my experience teaching at Hope House, I now feel much more confident working with English language learners back in the United States.

The third major lesson I learned throughout this experience was how to deal with self-doubt, especially as a first-year teacher. Every day I wondered if it were the right choice for me, a beginner violinist, to be teaching violin. I even admitted to the students on the first day of violin class that I had been studying music my entire life but had only studied violin for a few months. At the time, I thought I was explaining this to the students so that they would not have unrealistically high expectations of my violin skills. In hindsight, however, I realized this declaration had more to do with my own self doubt: By admitting my amateur status, I was giving myself the freedom to make mistakes. After days of imposter syndrome and lack of confidence hindering my success as a teacher—and thus hindering my students’ success on violin—I was determined to make a change. Specifically, I stopped fixating on my shortcomings as a violinist and string teacher, and I often talked to other teachers at Hope House to relieve stress.

What Can You Do?

It is my hope that sharing my experience will normalize the non-string educator’s competence in teaching strings and encourage other educators to embark upon similar journeys. Although some string musicians and educators may doubt a non-string educator’s ability to teach the violin with limited experience, I believe my personal efforts were successful, as I left my students with a lifelong love of music and the skills of violin technique and music literacy.

For non-string music educators, like myself, who find themselves with the opportunity to teach strings, I would recommend the following:

Take as many private lessons with a string player as you can.

Going through the process of learning a string instrument, even at a beginner level, will be extremely beneficial when modeling new concepts to string students and identifying common errors in their technique. The more you learn about string playing, the more knowledge and experience you will be able to pass on to your students.

Learn the basics of string instrument care and maintenance.

Ask your private teacher (or Google!) to teach you some basics about string maintenance and repair because these skills will come in handy more often than you realize. After all, once you are placed in front of a room full of eager string students, you are expected to be the expert on all things string-related.

Be nimble and ready to adapt.

Your experience transitioning into a new field of music will be entirely unique and impossible to predict. That being said, don’t let unpredictability stop you from embracing the challenge. Instead, face every obstacle with grace, determination, and an open mind.

Conclusion

After reading my story, I hope you feel empowered to help combat the string teacher shortage, especially if there are no string programs in your immediate community. If you are currently a non-string music educator, remember you are the biggest resource and the most readily available solution to the string teacher shortage. Your teaching credentials and passion for music education make you well-suited to transition into the string world.

Specifically, to current string educators, you also serve an invaluable purpose in this solution. Not only are you already teaching the next generation of string musicians, but you are also perfectly positioned to help non-string educators transition into the string world by mentoring them, giving them private lessons, and even connecting them to potential string educator positions that might otherwise go unfilled. After all, it was only from receiving help from a string educator that I was able to have this opportunity to teach violin in the first place.

About the author:

Michaela Johnson graduated from the University of Tennessee at Martin in 2019 with a major in Music Education and a focus in trumpet. Following her graduation, she began teaching general music and violin at the Hope House in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Johnson had to return to the United States earlier than planned, cutting her time in Thailand short. Now, she teaches general music at Pleasant Ridge Elementary School in Knoxville, Tennessee. In Knoxville, Johnson has resumed violin lessons with a private teacher in the hopes of continuing her work with violin at Hope House someday.