Andrea Dinkel

SEKMEA President

When I listen to a panel of highly experienced teachers reminiscing about their careers, the topic of “What I wish I would’ve known when I was starting out” often surfaces. Having served as a small school band director for eleven years, I already have a few things I wish I could’ve told myself. Starting a new music teaching job for a small school district can be tough for many reasons, especially when logistics seem to get in the way of music teaching. I hope that these ideas can help you organize and overcome the behind-the-scenes challenges so you and your students can enjoy success.

Develop an Informed Vision

A personal teaching philosophy is far from the only thing to consider when making long-term or even short-term plans for your students and program. Be flexible as you get to know your students, school, and community, as this will inform you on what is realistic, relevant, and achievable. Your program will likely not look like that of your high school, college, or even the district next door. This is because no two communities are exactly the same. For that reason, your vision needs to serve the students in front of you. Remember that our national music standards are really quite accommodating; how you go about accomplishing them is up to you, especially if you are the sole music teacher in your building.

Choose Goals

Working to fulfill a vision can be a lengthy process–think years or even decades–and requires a lot of working inner parts that each take their own amount of time and energy to develop. To help your program progress toward your vision, make small, attainable goals that your students and community can celebrate along the way. Students especially need to feel successful, and smaller goals will create a steady flow of positivity surrounding your program as it grows and changes.

Make a List

Writing a list of the things your program needs is a helpful way to keep goals organized and prioritize needs. When you create your document, categorize needs by urgency—things you need right now, things you need during the next summer/year, and finally, things that are needed as the program grows and develops down the line. Dividing the list in this manner will protect you from the mistake of tackling everything at once. (That’s unrealistic). The list will help you focus your efforts on the things that will be the most useful to your students right now. It also helps you not forget anything on the radar and miss an opportunity—sometimes an opportunity will present itself that doesn’t speak to an immediate need, but is something that will help with an eventual need.

Let the Literature Guide You

The literature you choose for your students–or the literature you don’t get to choose–will be a large part of your prioritizing and goal setting. Immerse yourself in our canon to find pieces that represent the students in front of you, the skills and techniques they have time to develop, and the equipment you have or can realistically attain. For example, when I was hired at my current district, there was a very limited amount of percussion: snare, bass, cymbals, and a pair of timpani. The timpani would only hold a couple of pitches (if the phase of the moon and the air quality were just right). So I picked contest literature that reflected my students’ abilities and the pitches the timpani could reach since I had no bass voices represented in the wind section at the time.

The following school year, I was cleared to fundraise for some instruments. In early September, I chose our spring contest pieces–two pieces that were playable with our existing equipment minus one thing: a set of concert chimes. This helped me know exactly what I needed to fundraise for and gave me the time necessary to get the instrument in our inventory by the time the students would need it in January. Finally, planning in this way ensured that we would be able to feature the new instrument at a concert so the audience could appreciate their importance, and the band could thank them for their support. I repeated this process each school year, and after five years, we not only had all the instruments in place to access most Grade 3 concert band and percussion ensemble literature but a supportive audience that better understood what they were listening for and felt connected to our success.

The Art of Asking

A thriving program is the product of the efforts of many. For that reason, we must learn how to ask when we have needs. It seems many of the people who have a hand in our fate don’t always speak our language–and that’s ok. When asking for assistance, be clear, kind, and generous with patience as you respond to further questions about your needs. Sometimes those questions can feel like rebuttals, but remember that when someone asks a question, it is usually because they don’t understand and would like to. Beware of discipline-specific jargon that can cause extra confusion and may needlessly cause your leaders to feel small. For example, when you find yourself in need of a new tuba, your principal will probably gasp at the thought of a $5,000 price tag only serving one student. Describing the need for a “balanced ensemble sound” may or may not work at first because of our specialized content language. However, pointing out that one single field goal post for the stadium costs upwards of $5,000 and is only used by two student-athletes in the fall during home games might help facilitate the understanding that certain equipment is crucial. We can’t win the game if we can’t earn the points due to a lack of necessary equipment.

Learn Who To Ask

We often default to asking our building principals when needs arise, but in reality, there are many people who make our jobs as music teachers possible. As teachers, we get agitated when a parent or community member asks a question or makes a complaint involving us that we could’ve easily taken care of had we only been aware. Remember that feeling, as going over someone’s head is an easy way to unintentionally cause others to feel hurt or accused. For example, if you need your classroom cleaned differently at night, start by asking your Head of Maintenance about options instead of going straight to your principal. Consider questions like these as you begin to notice the roles of those around you, and be careful to not go over anyone’s head. Is your need something you can take care of with the help of some parents or community members? Do you need administrative permission or support? Does your need fall under the umbrella of your school’s counselor? Are there other teachers in your district who have been through the same process and might have advice for you?

Learn When to Ask

If you have a large financial need on the horizon, begin planting seeds as soon as you know the details. Think of what your school leadership will want to know, and have multiple quotes and any logistic information in-hand for that first conversation. Ask at the beginning of the school year when there might be some resources. Ask again around Christmastime when the dust of the first semester has begun to settle, and the state of the year’s budget is better known. Ask again on July 1st when the fiscal year begins. If you are seeking a schedule change, the end of May is probably not the best time to ask. Collect and present good data toward the beginning of the school year so that your students’ needs are known. Have a discussion again at the end of the first semester so that needs are not forgotten. Schedule a meeting to discuss changes again well before Spring Break when those changes are actively being addressed throughout your building. Above all, keep asking as long as a need remains. So often, “no” really means “no, not now,” as opposed to “no, not ever.” Be tenacious and keep asking, as you may be the only music advocate for your students.

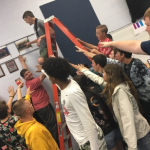

Showcase Achievements

A large part of advocating for your students is simply remaining visible. Did you have more students make an honor band than ever before? Great! Submit a post to your district’s Facebook page so your community can celebrate with your students. Did your request for a new musical instrument go through? Fantastic! Choose literature that will feature the instrument so the audience can see it and understand its importance. Did your band earn their first top rating at a festival in many years? Congratulations! That took a ton of work! Have your principal meet your students when they arrive back at the school to shake their hands and congratulate them, and submit a picture and paragraph to the local newspaper. Make sure your students are acknowledged at the next school pep assembly when they achieve great things.

Always Say, “Thank you”

Sincere and timely thank you’s are paramount in a cycle of support for your program. Always find someone to tell “Thank you” for their role(s) in helping your students achieve. Seek out and thank anyone who played a role in making it possible for your students to attend an event, achieve a goal, or have a better experience in music. This could include bus drivers, transportation directors, board office personnel, principals, custodians, parents, donors, and fellow teachers. Use “Thank you” and “supportiveness” as actual words in the thank you, because sometimes people don’t understand what supporting music is until they get thanked for it—then they begin to realize and make it a habit. Involve your students in the thank you process. This helps them learn to be courteous and appreciative of the efforts of others. For example, a thank you card that each student signs is simple and extremely effective.

Keep Good Data

Whether you have been tasked with maintaining an existing program, starting one from scratch, or righting the ship, one thing is certain: you must keep good data and learn to make sense of it. Data is always honest, shows you where you’ve been, where you are, and, when you connect those points, your trajectory. Those points can be encouraging when you feel you aren’t making the progress you expected, revealing when you notice things about your program or your teaching that need revision, and indispensable when you need to advocate for change.

One of my favorite forms of data in a band room is old festival pictures and plaques on the walls. When I became the band director for my current district, most of the data one might expect–concert programs, festival rubrics, old rosters, recordings–were all gone, but the thing that remained was a running line of annual photos from a local jazz festival that encircled the classroom. Those pictures told me that jazz was a big part of the culture of the program for nearly twenty years. The walls also told me that something happened after 1998 that made the pictures stop. That’s all I knew. But that was enough to begin forming a vision and a trajectory toward something that might be highly successful once again, so I made my list and got to work. The four-year process of getting the jazz band reinstated in the high school’s schedule deserves an article all to itself, so suffice it to say that the moment I got to hold my own group’s photo in my hand and watch my students hang it on the wall next to that 1998 photo was one of the proudest moments of my career thus far.

That photo represents the history and tradition of our program, smart and timely requests, huge support from the community, the trust of school leadership, tenacity from myself and my students, and about a million small achievements that had to happen along the way before that moment was possible.

Left Picture: First jazz band picture after a nearly 20-year hiatus

Begin creating and saving various forms of data as soon as you can, and make a habit of adding to the collection. Keep a copy of every program that your students are represented in–concerts, Veterans’ Day Assemblies, school musicals, local auditioned bands, festival rubrics, recordings. If you do not print your students’ names on concert programs, be sure to keep class rosters with instrumentation. Even keep copies of things like student disciplinary referrals if you think them relevant. These are all ways you can see growth and progress over time.

Right Picture: Celebrating success by starting a tradition of reaching together

Collecting data will also help the person who follows you know the program’s traditions and where the current students are in their musical journeys. Remember that a program does not stop with you–your students deserve the gift of this paper trail so that their future teachers can make the most informed decisions possible as soon as possible.

Finally, take lots of pictures. It is impressive how quickly memories begin to fade, and dates and specifics become hazy. Pictures really do say a thousand words. Reminding yourself and your students of the good times will help you build your music community, keep perspective, and stay positive during the process of change. If you catalog your pictures or videos into an annual band yearbook or video, be sure to give a copy to the school’s library so that those memories are less likely to “walk away” over time.

Stay

It is no secret that the realities of teaching can catch us off guard. Many young teachers do not stay in the profession past five years when the expectation of what the job is and the reality of the job at hand are simply too different to tolerate. Remember that you can mitigate that difference by breaking ominous tasks into achievable goals, letting others help you, and keeping lots of data. Soon you will see many successes and the accompanying confidence that you are a capable educator who is making a positive difference for your students.