This article first appeared in The Orff Echo Fall 2018 issue, Vol. 51, No. 1. © 2019 American Orff-Schulwerk Association: Chagrin Falls, OH. Used by permission.

ABSTRACT: The recorder has been an integral part of the Schulwerk since its beginning in the 1920s at the Güntherschule in Munich. This practical instrument can be used to enhance a variety of lessons in the music classroom. Seeing the recorder as a daily tool, rather than as the basis for a single instructional unit, can help creative teachers use it to enhance a wide array of musical experiences for their students.

It is a well-known story, but one worth retelling. In 1926, as Carl Orff was exploring an elemental approach to music and dance, he searched for melodic instruments to include in the percussion ensemble that accompanied the dancers at the Güntherschule. Although the gift of an African xylophone had sparked his imagination, there was as yet no way to produce a usable version. Musicologist Curt Sachs recommended recorders to be “the pipe to the drum, corresponding to historical development” (Orff, 1978, p. 96). A quartet of recorders was ordered but arrived with neither fingering charts nor playing instructions. Orff (1978) describes his colleague Gunild Keetman’s reaction: “Give me a recorder and I will find out how it works—in a month the lessons will begin” (p. 109). Keetman’s experiments with the instruments led to a rhythmic, improvisatory manner of playing that fit well with the new elemental music Orff envisioned.

The recorder has always been a central part of Orff Schulwerk instruction. It was one of Keetman’s favorite instruments for teaching and for dance. Of her 48 published volumes of music, 11 deal exclusively with recorders (alone or with percussion). In addition, many of her pieces in the five volumes of Music for Children include recorder parts.

Orff and Keetman’s students at the Güntherschule were young adults, whereas Orff Schulwerk teachers today typically work with younger children and need to utilize the recorder on a different, more elemental level while still striving to keep the spontaneity and joyfulness that Keetman’s students experienced. Whether we are teaching adults or children, though, the recorder is a wonderfully appropriate instrument for elemental music instruction. It is affordable, accessible, portable, and can be used to teach or reinforce most foundational music concepts. It is particularly useful in helping develop children’s small-muscle coordination and their singing voices. Even reluctant singers can become enthusiastic, confident participants when allowed to establish their sense of pitch through recorder playing.

Recorder in Everyday Use

In many elementary music classrooms the recorder is used primarily as a way of introducing the experience of playing in an instrumental ensemble or as the basis for a unit on notation. It is an effective tool for doing both, but that is by no means the end of its usefulness. As Brigitte Warner (1991), a student of Orff and Keetman who later established the Orff Schulwerk program at the Key School in Annapolis, Maryland, stated:

It is not by mere chance that the recorder occupies an important place in the Schulwerk instrumentation. With the exception of the human voice, it is the only non-percussive instrument in the Orff ensemble and, as is the case with the voice, its tone is produced by means of the breath. Not only is it well suited to smooth and sustained melodic flow, a feat difficult to achieve on the barred instruments, it also lends itself naturally to playing fast passages and to embellishing (the latter being a direct outgrowth of improvisation). Thus, in Orff Schulwerk the instrumental melody with a distinct style of its own begins with the recorder…. An elemental instrument, the recorder invites dancing and can even be played while dancing. In addition, its pure and light tone complements the sound texture of the barred instruments. (p. 224)

In other words, in addition to having qualities that make it ideal for certain kinds of music-making tasks, the recorder is a useful and adaptable tool for every aspect of what we teach in the Schulwerk.

Adapting recorder for wider use also means expanding its use across the grade levels. It is true that students do not possess the necessary motor skills to begin playing recorders until third or fourth grade, but that does not mean the instructor cannot introduce the instrument as an instructional tool as early as kindergarten. Modeling good musical practices is a central part of Orff instruction, and playing regularly for children for years before they are ready to play also tends to make the recorder just another part of the natural musical order. In addition, it helps us become better players; it is an article of faith among recorder enthusiasts that one major reason many teachers do not get around to teaching recorder is because they lack confidence in their own skills.

Looking at various elements and processes of the music curriculum, we can see how the recorder can become an integral part of the music class.

Melody and Singing

Recorders can not only play a melody by themselves, but also can double children’s voices or instrumental lines, providing an additional timbre to the classroom ensemble and supporting the singing voices. It is not necessary that recorders play the entire tune—they can often play just one section of the melody, or perhaps highlight a particular solfège or rhythm pattern whenever it occurs. Children with recorders can create an introduction or coda and, of course, can improvise, either freely or to a given text or rhythm pattern.

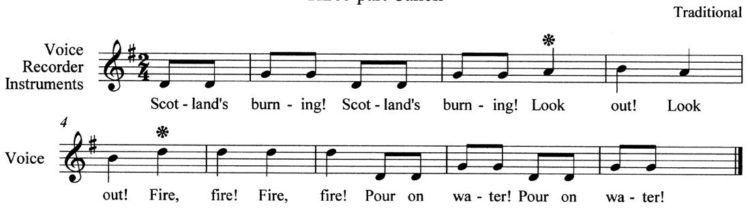

The recorder is also a highly effective accessory when students are working in pairs or in small groups. It can be the response in a call-and-response song, such as “oo-oo-oo-oo” in Skin and Bones. When learning a canonic melody such as Scotland’s Burning, the students may sit in pairs at the barred instruments with one child singing and playing with mallets while the other plays on recorder. The song can then be performed in a three- or four-voice canon, for instance, using recorders along with singing, xylophones, and glockenspiels (see Figure 1).

Harmony

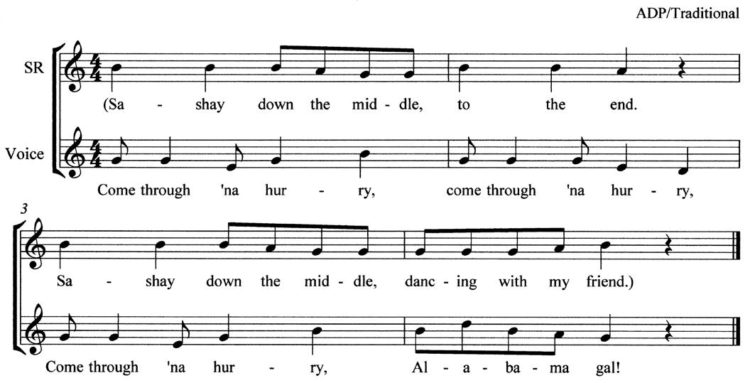

Recorders have been playing in harmony in matched consorts or in mixed ensembles since the Renaissance. In the music class they can provide ostinati with barred instruments or by themselves; and because of their sustaining ability, recorders are excellent choices to perform simple and moving drones. Melodic ornamentation—playing in parallel thirds or triads—can provide a challenge for more advanced students and create an interesting variation to many tunes. More advanced examples of parallelism may be seen in Bergerettes 1 and 2 in Music for Children, Volume V (Orff & Keetman, 1954). As with much of the material in the Volumes, Bergerettes may be transposed to match students’ range or played in the original key, for example, by introducing alto and other F recorders. Recorders can play a countermelody to the children’s singing, providing melodic contrast and harmonic interest (see Figure 2).

Form

Recorders offer an additional timbre to the classroom ensemble; therefore, they can be used to reinforce students’ understanding of form. In an abac song, such as The Canoe Song, the notes B, A, G, and E can be played on the a motif on the recorder while the b and c motives are played on the barred instruments. In larger forms, recorders can be responsible for entire sections:

INTRO Recorders and hand drums

- A Singing with instrumental accompaniment

- B Xylophone improvisation on the rhythm of a short poem

- A Singing a cappella

- C Recorders playing a tune developed in class—using the notes of the A melody

- A Singing with instrumental accompaniment

- D Hand drum/Body percussion piece developed in class

- A Singing, recorders, and hand drums with instrumental accompaniment

Movement

Movement is an essential part of daily Orff Schulwerk instruction, both as a means for students to internalize a sense of time, rhythm, or form and as another mode of creative expression. Many music teachers assume that recorder instruction is incompatible with movement and is more appropriately conducted with students seated behind music stands. Gunild Keetman was not one of them, however. In Elemental Recorder Playing, Keetman encouraged moving with the recorder from the early stages of instruction: “… one can begin very early to combine recorder playing with simple movement patterns in space. [This leads] to a satisfying musical/physical union that is reflected in a vitality of playing even when not moving in space” (Keetman & Ronnefeld, 1999, p. 24).

Recorder players can accompany, lead, or follow movement in various ways. A group of recorders and other instruments can be the “dance band” for a folk dance such as Alabama Gal. A recorder player can improvise to another student’s movement, using a few notes and letting the articulation reflect the smoothness or angularity of the movement. Conversely, the recorder playing can dictate these elements to the dancer.

As Keetman describes, students can also be moving while playing, with proper guidance, of course! While moving in a controlled manner, players may match or contrast the level, flow, and force of the movement with the instrument’s pitch, articulation, and volume, within the recorder’s limit. Or, more simply, the students may alternate movement and playing.

Sound gestures can be used to “conduct” recorder players. A snap might represent the note B while claps, pats, and steps might represent A, G, and E, respectively. The quality of the sound gesture should be reflected in the playing of the recorder.

Improvisation

Carl Orff was very clear: “Improvisation is the starting point of elemental music making” (Orff, 1978, p.22). Recorder is an ideal instrument to foster improvisation in our students—from the very first lesson. As Isabel Carley (2011), first editor of The Orff Echo, stated, “Even the youngest participants, or those with little musical training, naturally become self-assured as their own invented music becomes part of a larger piece that is shared with the group” (p. v).

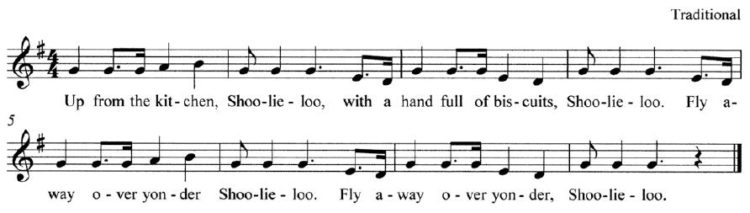

In a song such as Shoo-Lie-Loo, the children may move while the teacher sings, then stop and sing each “shoo-lie-loo.” This activity would be repeated having the class play their part on the note G with a “doo” tonguing. The students may replace “shoolie-loo” with food items, such as “peanut-butter sandwiches,” thereby improvising different rhythm patterns (Purdum, 2014, pp. 28-29).

After learning a few more pitches, the children can improvise on the rhythm of a nursery rhyme. The teacher shows a few notes in a visual, in staff notation, or just the names of the pitches. The class plays the entire rhythm on each pitch, listening for good tone production and clear tonguing. Next they play the rhythm again, changing pitches as the teacher or a student indicates. In the final step, the students make their own decisions on when to change pitches, thereby each creating their own tune. “Solos Here for Everyone” in Music for Children, Volume I (Orff & Keetman, 1950), can be the vehicle for students to share their ideas: The first four measures can be the A section of a chain rondo, with individuals soloing on the notes A, G, E—and possibly D and C—between repetitions.

Literacy

Music is best learned in the same way as a language. Babies learn to speak by listening, playing with sounds, imitating others, and then using language to convey ideas before they learn to read. In a similar manner, children will be ready to read music notation on the recorder only after they have had some success exploring the recorder’s sounds, listening to recorder playing, imitating the teacher, and learning songs. Introducing the notation of a song after it has been learned will be more meaningful to beginning students than trying to decipher the notation and play at the same time.

The recorder is seldom the best instrument for learning to read notation. Students are learning new fingerings, new ways of blowing and of tonguing, and are often struggling with fine-motor control. Asking them to read a new set of symbols at the same time will often result in frustration. Most children will have more initial success learning notation from barred instruments, from singing, or from both.

This does not mean, however, that notation shouldn’t be used. Pitch patterns in the songs students play can be isolated and displayed visually. Students may learn a short pattern and play it whenever it occurs in a song. Providing them with a written pitch palette showing the notes suitable for improvisation can be helpful and will tend to reinforce their understanding of where the pitches appear on the staff. Likewise, students can view rhythm patterns, speak them, and then use them as the framework for improvisation.

Practical Considerations

If the recorders are being used throughout the year, students must bring them to class or they need to be stored in the music room. If they are kept at school, each class needs its own space where students can pick up and return the instruments each day. If they will be taking the recorders home, teachers should make provision for those who forget or lose their instruments. Having several loaner instruments available saves a lot of class time and “drama.” The student quietly takes a recorder from the “clean” bucket, uses it in class, and returns it to the “used” bucket. Of course instruments are sanitized after each use.

The other major consideration is recorder volume. The teacher needs to be pro-active on this matter, setting boundaries and expectations from the start of instruction. Children who play at inappropriate times can be corrected in a firm but gentle manner. Continue to remind them to listen to their playing and not produce “ugly” sounds. Not having all the students play at the same time helps in this regard. Divide the class into three or four groups that rotate through different media: movement, barred instruments, recorders, singing. When learning a melody, a third of the class can play on xylophones while another third plays recorders and the final group sings the pitch names. Change roles every few minutes (Purdum, 2014).

Conclusion

Recorder has been an integral part of Orff Schulwerk since its beginning. Children love the recorder and can do so much with it. As the role of the recorder is expanded through regular use, both students and teachers can refine their playing, listening, and improvisational skills through the joy of making music on their own instrument. Rather than only a few weeks of instruction, why not integrate this versatile instrument into our lessons and broaden students’ musicality as we enhance the sound of our classroom ensemble?

R E F E R E N C E S

- Carley, I. (2011). Recorder improvisation and technique, book one. (4th Ed.). Charlottesville, VA: Brasstown Press.

- Keetman, G. & Ronnefeld, M. (1999). Elemental recorder playing, teacher’s book. Mainz: Schott Music Corporation.

- Orff, C. (1978). The Schulwerk. (M. Murray, Trans.). New York, NY: Schott Music Corporation.

- Orff, C. & Keetman, G. (1950). Orff-Schulwerk: Music for children, vol. i. (M. Murray, Ed.). London: Schott & Co. Ltd.

- Orff, C. & Keetman, G. (1954). Orff-Schulwerk: Music for children, vol. v. (M. Murray, Ed.). London: Schott & Co. Ltd.

- Purdum, A. (2014). Recorder: A creative curriculum. Cedar Falls, IA: Cedar River Music.

- Warner, B. (1991). Orff-Schulwerk: Applications for the classroom. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Alan Purdum is retired from Grand Valley Schools in Orwell, Ohio, where he taught music for 38 years, predominantly kindergarten through Grade 5. He is a past president of the Greater Cleveland Chapter and served on the AOSA Board of Trustees as a regional representative and as recording secretary. Alan has taught recorder at all three levels of Orff Schulwerk Teacher Education. He is a member of the American Recorder Society, plays regularly with the Rosewood Consort, and is the author of Recorder: A Creative Sequence, a complete curriculum for recorder in the elementary school.